Have you thought about what living off-grid would actually feel like on a day-to-day basis?

What I Wish I Knew Before Trying To Live Off‑Grid (Beginner Reality Check)

You probably imagine freedom, quiet, and a simpler life when you think about living off-grid. That vision is part of the appeal, but the reality includes a lot of planning, trade-offs, ongoing maintenance, and unexpected constraints. This guide gives an honest, practical breakdown so you can make smarter decisions before you commit.

A realistic overview: what “off‑grid” really means

You should first define what off‑grid means to you. For some people it means no utility connections at all. For others it means partial independence — like having alternative power and water but still relying on a road, mail service, and occasional trips to town.

You’ll need to weigh degrees of independence against convenience, cost, and safety. Knowing your end goal helps you design systems that match your priorities.

Degrees of off‑grid living

You can aim for full physical independence, partial independence, or lifestyle independence (less consumption, but still connected to utilities). Each level has different legal, financial, and technical implications.

You should decide which level fits your priorities and tolerance for complexity.

Planning: the biggest upfront step

Good outcomes start with careful planning. You’ll save time, money, and frustration if you map out your needs, capabilities, and timeline before buying land or building systems.

Your plan should include budget, timeline, required permits, resource assessments (water, sun, wind), skill gaps, and contingency plans.

Create a realistic budget and timeline

Underestimating costs and time is a common mistake. You should account for land, site prep, systems (power, water, sewer), tools, permit fees, transportation, and a contingency fund (25–40% recommended).

Be prepared: projects often take months longer than expected, especially in remote areas with seasonal weather constraints.

Skills and labor requirements

You’ll need a mix of skills: basic construction, electrical, plumbing, mechanical, gardening, and first aid. Identify which skills you have and which you’ll hire. Labor in remote areas can be costly and scheduling specialists can cause delays.

Plan hands-on learning time if you intend to do much of the work yourself. Practical experience reduces mistakes and increases safety.

Legalities and zoning: don’t assume freedom

Zoning laws, building codes, and permit requirements can limit how you build and what systems you install. You may think off‑grid living avoids bureaucracy, but local rules often still apply.

Contact local authorities or hire a local consultant to understand restrictions on dwellings, septic systems, water use, livestock, and renewable energy installations.

Typical legal hurdles

You’ll commonly encounter rules about minimum dwelling size, minimum distance from property lines, septic permits, well drilling permits, and road or driveway permits. Some jurisdictions restrict living in tiny homes or non-permanent structures.

Make sure you know these before buying land or placing a structure.

Site selection: resources and constraints

Choosing the right property affects every system you’ll build. Water availability, solar exposure, topography, soil type, wind patterns, access roads, and proximity to towns matter.

You should assess natural resources and risks (flooding, fire, avalanche, landslide). Prioritize properties with reliable water and easy energy potential unless you’re prepared to invest heavily in alternatives.

Water sources and reliability

Water is the most critical resource. Options include wells, springs, surface water (streams/lakes), rainwater harvesting, and hauling water.

- Wells: most reliable if aquifer is good, but drilling costs vary and yield is not guaranteed.

- Springs: can provide high quality, but flow can vary seasonally.

- Surface water: may require filtration and treatment.

- Rainwater: depends on rainfall patterns and roof catchment size.

- Water hauling: simple but labor-intensive and costly long term.

Test water quantity and quality before purchase when possible.

Sun and wind exposure

Solar and wind are your primary renewable energy sources. Assess average sun hours and wind speed. South-facing clearings are best for solar panels in the Northern Hemisphere.

Keep in mind shading from trees or nearby hills can dramatically reduce solar efficiency. If solar exposure is limited, wind or hybrid systems may make more sense.

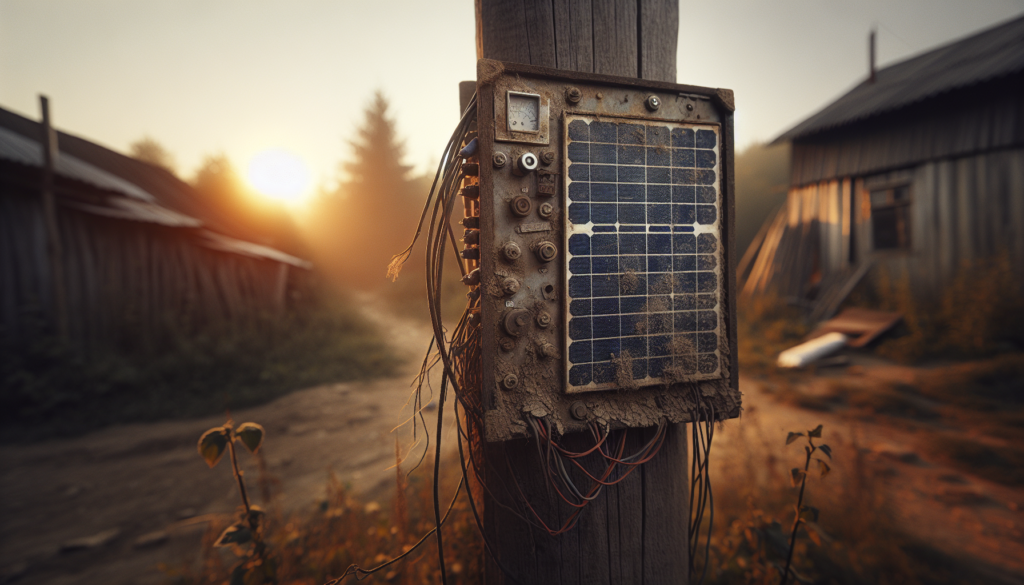

Power systems: sizing and reliability

Electricity is a top concern. You’ll need to decide on generation (solar, wind, hydro, generator), storage (batteries), and backup options.

Sizing your system properly avoids frustration. Start with a realistic load calculation based on actual devices you’ll use.

How to calculate your power needs

List every device you expect to run, its wattage, and expected daily hours. Multiply to get daily watt-hours. Add a buffer for inefficiencies and future use (20–50%).

Example:

- Refrigerator: 800 Wh/day

- Lighting (LED): 200 Wh/day

- Laptop/phone charging: 100 Wh/day

- Water pump: 300 Wh/day (intermittent) Total: 1,400 Wh/day (+ buffer)

This helps you determine solar array size and battery capacity.

Components and options

You’ll choose among:

- Solar panels: predictable and low maintenance.

- Wind turbines: useful if average wind speeds are consistently above ~10 mph.

- Micro‑hydro: excellent if you have a reliable flowing water source.

- Generators: diesel/petrol for backup or primary power in low-sun/wind seasons.

Batteries:

- Lead-acid (AGM, flooded): cheaper upfront, heavier, shorter lifespan, more maintenance.

- Lithium (LiFePO4): more expensive upfront, longer life, better depth-of-discharge, lighter.

- Other chemistries: evolving, but LiFePO4 is common for off-grid.

Inverter and charge controllers must be sized to handle peak loads and charging currents.

Table: Quick comparison of common off‑grid power options

| Option | Typical Use | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|---|

| Solar PV | Primary electricity | Low maintenance, scalable | Requires sunlight, panels need space |

| Wind turbine | Complement solar in windy areas | Can generate at night | Requires steady winds, maintenance |

| Micro-hydro | Continuous power near streams | High reliability, consistent | Needs suitable site, environmental permits |

| Diesel/gas generator | Backup or primary | High power on demand | Fuel costs, maintenance, noise |

| Batteries (lead-acid) | Storage | Lower cost | Shorter life, maintenance |

| Batteries (LiFePO4) | Storage | Long life, deep discharge | Higher cost |

Water systems: quantity, quality, and treatment

Your water strategy must address supply, storage, pressure, and treatment. Clean drinking water is non-negotiable for health.

You’ll likely combine sources and systems: a primary supply (well or spring), storage tanks, filtration, UV or chemical treatment, and a backup supply.

Sizing water storage

Calculate daily water needs per person (conservative off-grid use 10–20 gallons/day; comfort use 50+ gallons/day). Multiply by the number of days you want to store for (e.g., 7–14 days).

Example:

- 2 people x 15 gal/day x 7 days = 210 gallons minimum Increase storage for gardening, livestock, or dry-season buffering.

Filtration and treatment steps

Common multi-stage approach:

- Sediment filtration (removes grit and particles).

- Activated carbon (removes odors, organic chemicals).

- Reverse osmosis (optional for high purity).

- UV sterilization or chlorination for pathogen control.

Test water for bacteria, nitrates, heavy metals, and hardness before selecting treatment.

Sewage and waste: sanitation options

Handling human waste is essential for health and environmental protection. Options include septic systems, composting toilets, incinerating toilets, and graywater systems.

Each option has regulatory implications; septic systems often require permits and specific soil conditions.

Pros and cons of common sanitation systems

- Septic systems: effective when soil and site conditions permit; requires maintenance (pumping) and can fail in high water table areas.

- Composting toilets: low water use, produce usable compost if managed correctly; need proper ventilation and monitoring.

- Incinerating toilets: kill pathogens with heat, require electricity or fuel; convenience at the cost of energy.

- Graywater systems: reuse lightly soiled water for irrigation; must follow local regulations and safe practices.

Plan for odor control, pathogen management, and regular maintenance.

Heating and cooling: comfort without constant grid power

Heating and cooling are major energy loads. Your climate determines the approach: passive design, insulation, thermal mass, wood stoves, propane, or pellet stoves.

Passive solar design, high insulation (R-values), and airtightness reduce energy needs dramatically.

Heating options and considerations

- Wood stoves: effective and affordable in wood-rich areas but require fuel supply and chimney maintenance.

- Propane/kerosene: clean-burning but requires fuel deliveries.

- Heat pumps: efficient if you have electricity, viable with larger solar/battery systems.

- Radiant heating and thermal mass: passive solutions that work well with solar gains.

Insulation and air sealing offer the best return on investment for comfort and lower fuel use.

Food production: gardening, livestock, and provisioning

Growing food reduces dependence on stores, but you’ll need time, knowledge, and land to produce a meaningful portion of your diet.

Start small and scale up. Consider season extension (greenhouses), preserving techniques, and companion planting to increase yields.

Realistic expectations for yields

Food production depends on soil quality, climate, water availability, and your time. A single person might produce a substantial portion of vegetables on 0.1–0.5 acres with intensive methods; producing most calories (grains, legumes) typically requires more land.

If you plan livestock, account for feed, shelter, water, fencing, and veterinary care.

Preservation and storage

You’ll need ways to store and preserve food: canning, drying, smoking, fermentation, root cellars, and freezer space (requires reliable power). Learn preservation skills before your first large harvest.

Tools, equipment, and spare parts

You’ll depend on tools and small equipment. Keep a well-stocked toolkit, commonly used spare parts for pumps, batteries, solar controllers, hoses, and basic mechanical spare parts.

A list of critical spares reduces downtime and keeps you safe in remote locations.

Essential tools checklist (examples)

- Basic hand tools: hammers, screwdrivers, pliers, wrenches

- Power tools: circular saw, drill, reciprocating saw

- Plumbing tools: pipe wrenches, fittings, sealants

- Electrical tools: multimeter, wire strippers, fuses

- Emergency gear: chainsaw, generator, first aid kit

Invest in quality tools; they last longer and reduce frustration.

Connectivity and communication

Internet and phone service can be limited off-grid. If you need remote work, emergency contact, or schooling, verify options: cellular signal, satellite internet, or long-range Wi-Fi.

Plan for redundancy — a satellite hotspot or satellite phone can be invaluable in emergencies.

Options for staying connected

- Cellular boosters: improve weak signals if a tower is nearby.

- Satellite internet (e.g., Starlink, VSAT): reliable but costs and latency vary.

- Long-range Wi-Fi: connects to a distant hotspot, works if line of sight exists.

- Two-way radios and satellite messengers: low-bandwidth but useful for emergencies.

Health, safety, and emergency planning

Living remote often means longer response times for emergency services. Prepare for medical issues, fires, severe weather, and equipment failure.

Create emergency plans, stock medical supplies, and maintain skills (first aid, CPR, fire suppression).

Emergency kit essentials

Keep a comprehensive kit accessible:

- First aid supplies and prescription medications

- Emergency water and food for several days

- Fire extinguisher, smoke/CO detectors with battery backups

- Flashlights, radios, and spare batteries

- Maps, compass, and multi-tool

Practice emergency drills so everyone knows the plan.

Community and social aspects

You may value solitude, but living off-grid can be socially isolating. Proximity to neighbors, local communities, and support networks matters for trade, help, and companionship.

Plan how you’ll maintain social ties, access services, and handle loneliness. Bartering and mutual aid with nearby residents can be highly valuable.

Financial reality and return on investment

Off-grid projects often have high upfront costs and long payback periods. Compare costs of grid connection versus off-grid infrastructure before deciding.

You should also consider ongoing costs: fuel, maintenance, replacement parts, taxes, insurance, and transport.

Factors affecting long-term costs

- Climate: more extreme climates need more energy for heating/cooling.

- Resource reliability: poor water or solar potential increases costs.

- Lifestyle choices: modern appliances and conveniences raise energy demand.

- Maintenance: batteries and generators need replacement on predictable schedules.

Environmental and ethical considerations

Off-grid living can reduce environmental impact, but poor planning (e.g., cutting trees recklessly, improper waste disposal) can harm ecosystems.

You should aim for sustainable harvesting, responsible water use, and minimizing landscape alteration.

Seasonal realities: plan for extremes

Many off-grid systems behave differently in winter, rainy seasons, or drought. Cold temperatures reduce battery performance, snow can cover solar panels, and dry seasons stress water supplies.

Account for worst-case seasonal performance when sizing systems and planning storage.

Common mistakes and how to avoid them

You’ll learn faster by avoiding common pitfalls:

- Underestimating energy and water needs

- Buying land without testing water access or sun exposure

- Ignoring permits and local rules

- Skimping on battery quality or storage capacity

- Overpromising self-sufficiency too quickly

Be conservative in your estimates and build redundancy.

Staged implementation: reduce risk and cost

You don’t have to go 100% off-grid on day one. Implement systems in stages:

- Secure water and shelter.

- Add reliable power (small solar + battery + generator).

- Improve insulation and passive systems.

- Expand food production and waste systems.

- Gradually move toward increased independence.

Staging allows you to learn, refine, and budget over time.

Example staged timeline (first 2 years)

| Stage | Focus | Typical timeframe |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Basic shelter, water access, sanitation | 0–6 months |

| 2 | Primary power system (small solar + battery), heating | 6–12 months |

| 3 | Expand power/storage, garden setup, tool acquisition | 12–18 months |

| 4 | Food preservation, livestock, secondary systems | 18–24 months |

Adjust pace to your budget, weather seasons, and skill growth.

Resale and changing plans

Properties and custom systems can affect resale value. Some off-grid features are attractive to buyers, while others limit market appeal.

Document systems, maintenance records, and installation specifications to make future transfers easier.

Mental and lifestyle adjustments

You’ll face new routines and constraints. Time management changes: chores like chopping wood, maintaining batteries, or hauling water become part of daily life.

You should value flexibility, patience, and problem-solving skills. Embrace a mindset of planning, redundancy, and learning from mistakes.

Checklist before you commit

Use this checklist to reduce surprises:

- Assess water availability and test quality

- Verify solar exposure and wind patterns

- Check local zoning and permit requirements

- Create a realistic budget with contingency

- List essential skills and arrange training or contractors

- Plan sanitation and wastewater management

- Calculate realistic energy loads and storage needs

- Prepare emergency plans and stock supplies

- Ensure communication options for emergencies

- Plan for seasonal variations and backups

- Start with staged implementation and document everything

Case studies and examples

Real-world examples help you see trade-offs. Here are short, anonymized summaries of typical scenarios.

- Mountain cabin: excellent solar in summer, heavy snow hides panels in winter. Solution: panels on pole mounts above snow level, generator backup, large wood supply, and remote road maintenance plan.

- Desert homestead: abundant sun, scarce water. Solution: large rainwater catchment and graywater irrigation, drip irrigation, and high-efficiency appliances.

- Forest river property: reliable micro-hydro potential, but legal permitting required for stream alterations. Solution: micro-hydro paired with battery storage and careful environmental review.

Each context requires tailored solutions.

Resources for learning and support

You’ll benefit from targeted learning:

- Local building departments and county planners for zoning and permits

- Renewable energy installers and battery suppliers for system design

- Agricultural extension services for soil testing and crop advice

- Wilderness first aid and emergency preparedness courses

- Online forums and local homesteading groups for practical tips and equipment recommendations

Seek local expertise early.

Final thoughts and realistic encouragement

Living off-grid can be deeply rewarding, but it’s not a romantic shortcut. You’ll gain independence, confidence, and practical skills — but you’ll also manage ongoing maintenance, unexpected repairs, and limitations. The best results come from careful planning, realistic expectations, conservative system sizing, and staged implementation.

You can make this transition successfully by taking small, deliberate steps: learn core skills, secure critical resources like water and shelter first, and build redundancy into power and safety systems. Make friends with neighbors and local professionals; social capital is as valuable as any tool.

If you move forward with humility, preparation, and patience, you’ll find the off-grid lifestyle both manageable and fulfilling.